CONCENTRIC TRAINING

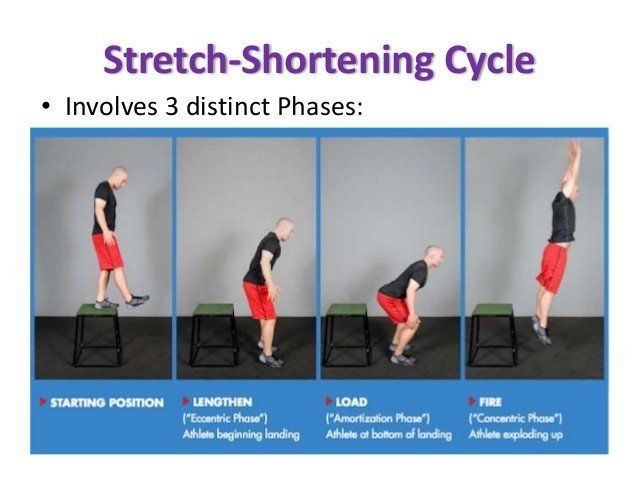

STRETCH SHORTENING CYCLE Pt. 3

CONCENTRIC MOVEMENT

The concentric phase is the final portion of the stretch shortening cycle, this is when the muscle length shortens. It is during this portion of dynamic movement that the muscle is producing enough force to overcome the load imposed upon it and contract. The concentric phase takes place immediately after the isometric phase, which is the brief transition after the eccentric phase.

IMPORTANCE OF THE CONCENTRIC PHASE

From an athletic performance standpoint, the concentric phase is by far the most important. It is how all performance is evaluated, for example: the weight snatched, the 40 yard sprint time, and the vertical jump height. It is the portion of dynamic movement we spectate in sport.

A term often used in to explain an athlete’s concentric ability is Rate of Force Development (RFD) or explosive strength. Rate of force development is how rapidly an athlete can generate force to overcome an imposed load. In order for RFD to be maximized the neuromuscular system should be looked at as a whole. All muscles working to produce one single dynamic movement need to be synchronized and coordinated.

RATE OF FORCE DEVELOPMENT ESSENTIALS

Coordination both within the fibers of the same muscle group and between different muscle group are essential for efficient dynamic movement.

Intramuscular coordination is the firing pattern of fibers within an individual muscle. The three factors that determine this are motor unit recruitment, rate coding, and rate coupling. Motor unit recruitment is the maximum number of motor units that can be recruited. The best form of exercise for improving this is overcoming isometrics. Rate coding is the frequency at which motor neurons are sent to the brain, which tell the muscle to fire. Lastly rate coupling is the number of cross bridges formed within the muscle, a higher number of cross bridges equals a higher amount of force produced.

Intermuscular Coordination is the coordination between different muscle groups in your body to produce one dynamic movement. The two factor that determine this are inhibition/disinhibition and synchronization.

In every dynamic action there is antagonist muscle and agonist muscle. The antagonist is the muscle that is eccentrically contracting to absorb force and the agonist is the muscle that is concentrically contracting to produce force. An example of this is when performing the concentric portion of a bicep curl, the bicep is the agonist muscle producing the force and the triceps is the antagonist muscle that is absorbing force. In order for RFD to be maximized the force exerted by the antagonist muscle must be inhibited, so more force can be produced by the agonist muscle. The human body only has so much energy it can provide to the muscles to produce force, make sure your supplying it to the right ones! This is where synchronization ties in, to be the most explosive athlete in competition you must have the ability to turn the correct muscles on and off at the right times. This gives you the edge in creating force faster than your opponents.

STRETCH SHORTENING CYCLE OVERVIEW

· Eccentric: the amount of force you can produce is only as much as you can store

· Isometric: must take place rapidly and be efficient, so no energy is lost during transition

· Concentric: neuromuscular system must be coordinated for RFD to be maximized

I hope the articles the past few weeks have been helpful in understanding why movements are programmed to emphasize particular portions of the stretch shortening cycle. They all tie in together and are very important for progress in force production. If one portion of the stretch shortening cycle is left untrained, it will be the weak link and what impedes progress, so make sure you train to ABSROB and PRODUCE force efficiently!

Source

-Triphasic Training

-By: Cal Dietz and Ben Peterson

***Participation in Any At Home WOD or Live Zoom Class or the use of any other information on this website or digital platform managed by CrossFit Lake Effect signifies that you have read and agree to this Waiver and Release of Liability even if it is not signed.